Advanced x86. BIOS and System Management Mode Internals Reset Vector презентация

Содержание

- 2. All materials are licensed under a Creative Commons “Share Alike” license.

- 3. Reset Vector Execution Environment

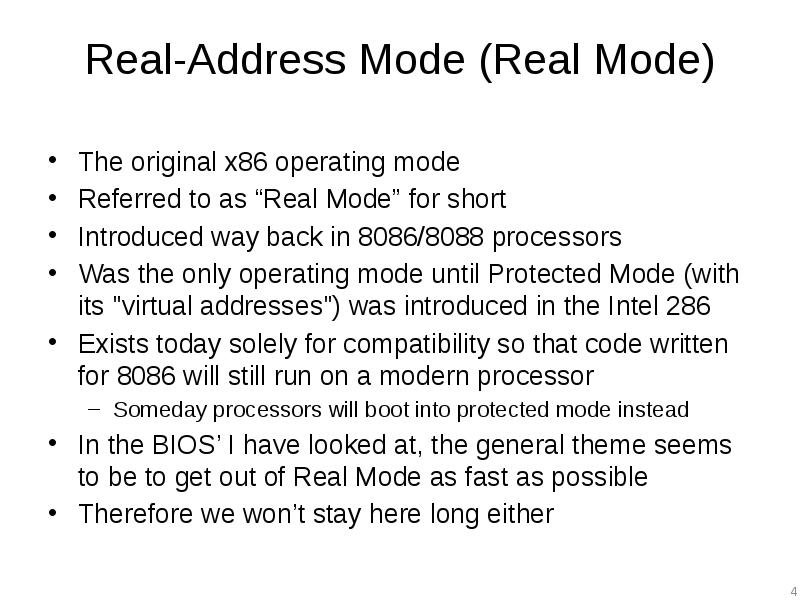

- 4. Real-Address Mode (Real Mode) The original x86 operating mode Referred to

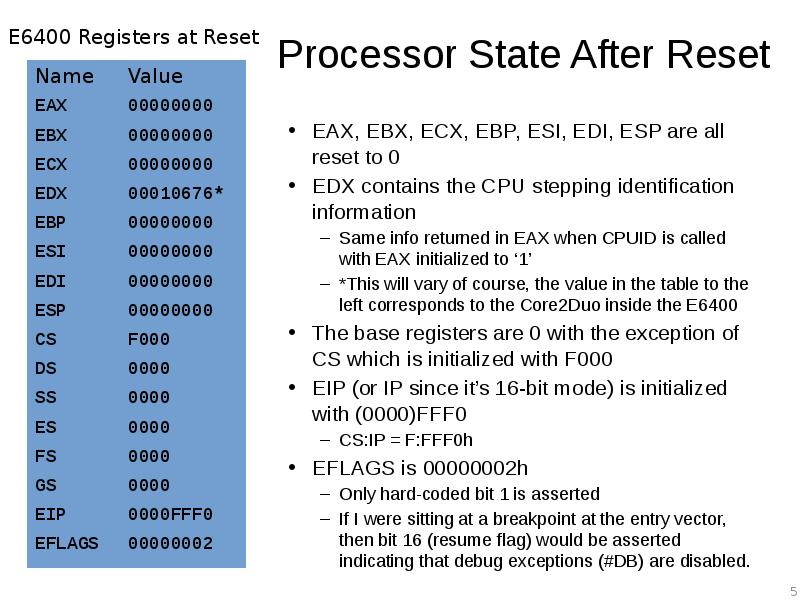

- 5. Processor State After Reset EAX, EBX, ECX, EBP, ESI, EDI, ESP

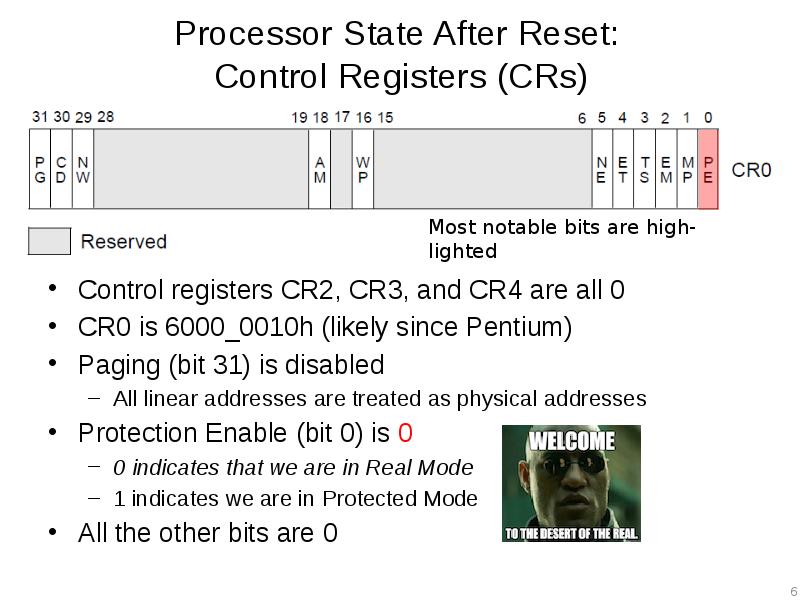

- 6. Processor State After Reset: Control Registers (CRs) Control registers CR2, CR3,

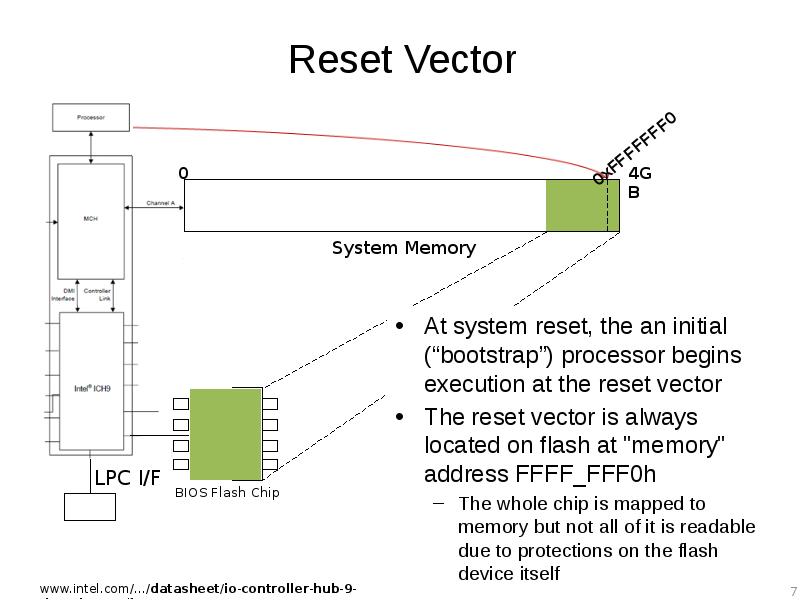

- 7. Reset Vector At system reset, the an initial (“bootstrap”) processor begins

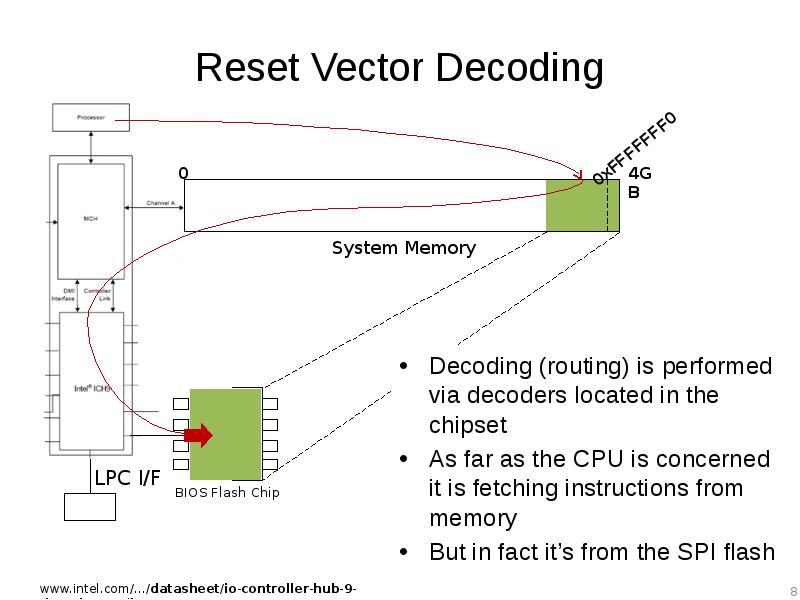

- 8. Reset Vector Decoding Decoding (routing) is performed via decoders located in

- 9. Aside: Forensics People If the top of memory always contains a

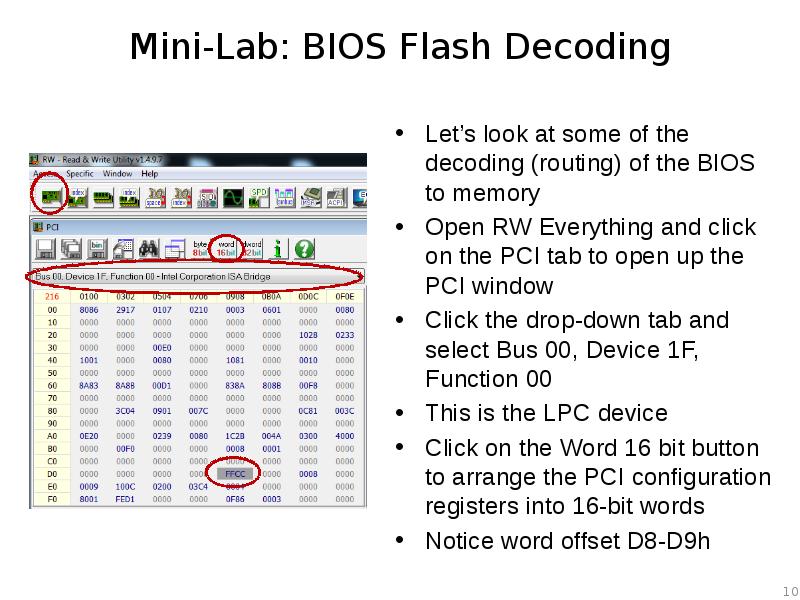

- 10. Mini-Lab: BIOS Flash Decoding Let’s look at some of the decoding

- 11. Mini-Lab: BIOS Flash Decoding Offset D8-D9h is FWH_DEC_EN1 As stated, this

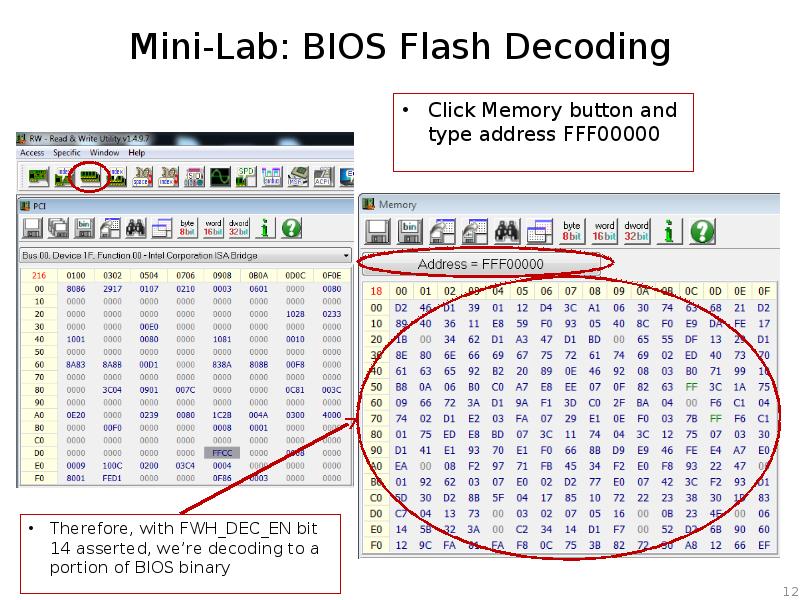

- 12. Mini-Lab: BIOS Flash Decoding Therefore, with FWH_DEC_EN bit 14 asserted, we’re

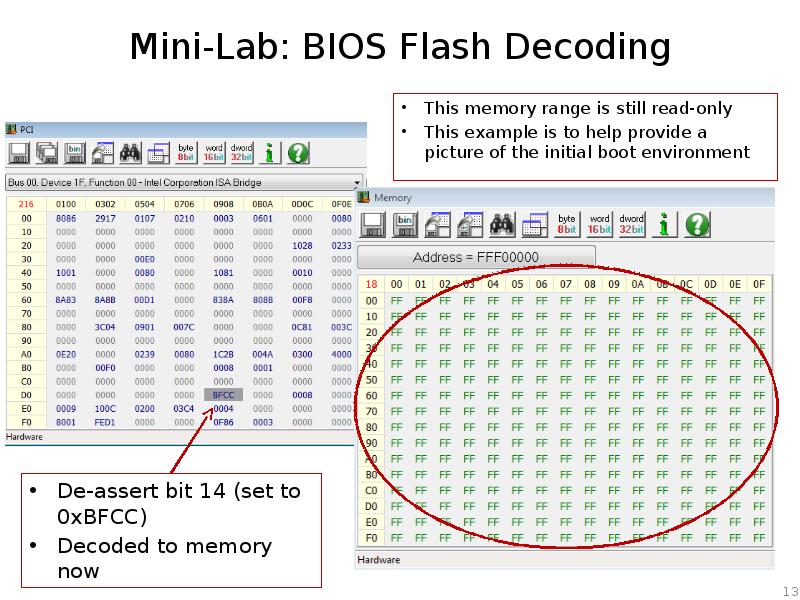

- 13. Mini-Lab: BIOS Flash Decoding

- 14. Mini-Lab: BIOS Flash Decoding Reset it back to 0xFFCC Couple of

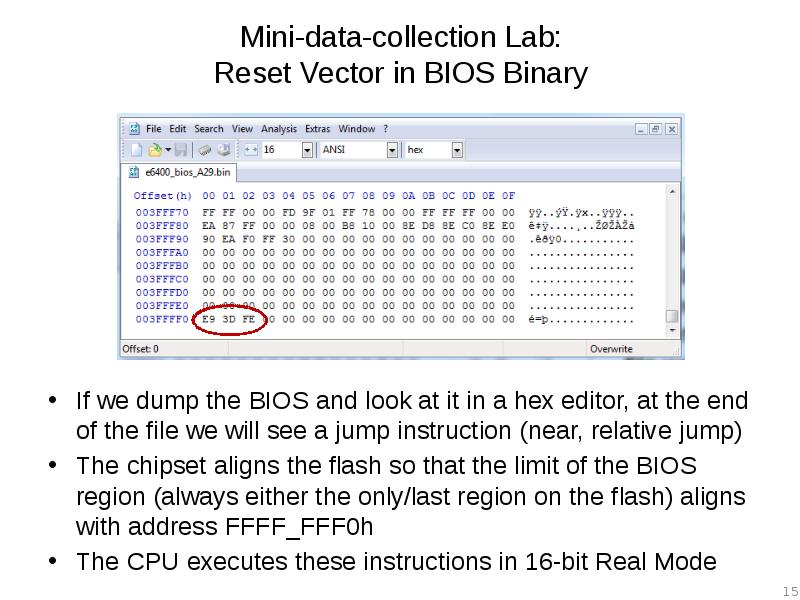

- 15. Mini-data-collection Lab: Reset Vector in BIOS Binary If we dump the

- 16. Real Mode Memory 16-bit operating mode Segmented memory model When operating

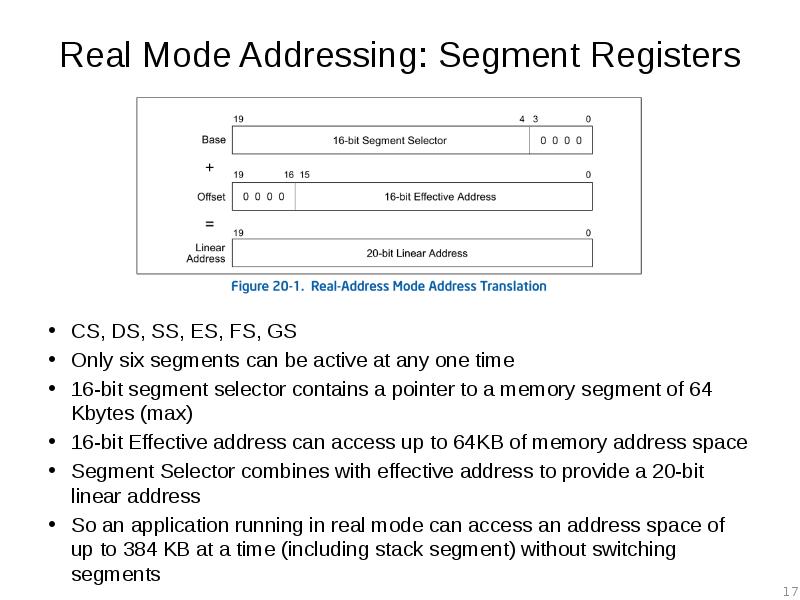

- 17. Real Mode Addressing: Segment Registers CS, DS, SS, ES, FS, GS

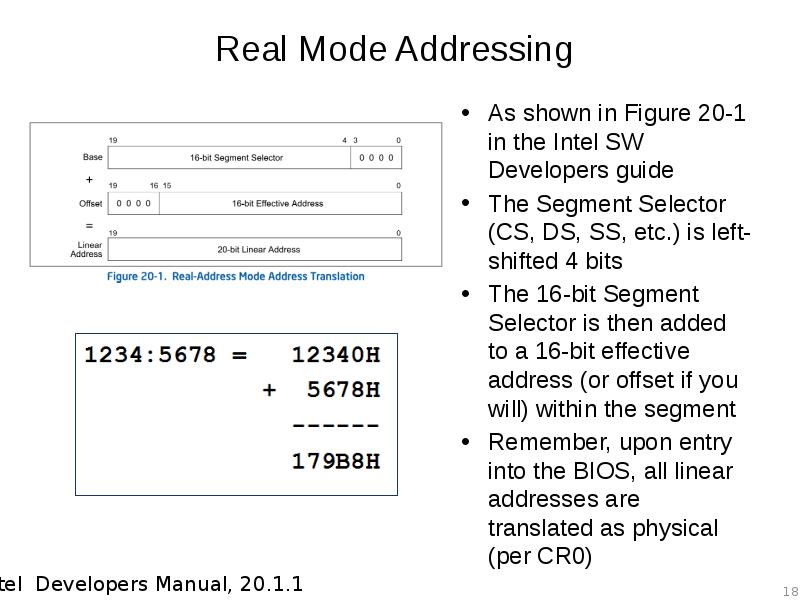

- 18. Real Mode Addressing As shown in Figure 20-1 in the Intel

- 19. Real Mode Addressing Problem: Overlap Addresses in different segments can overlap

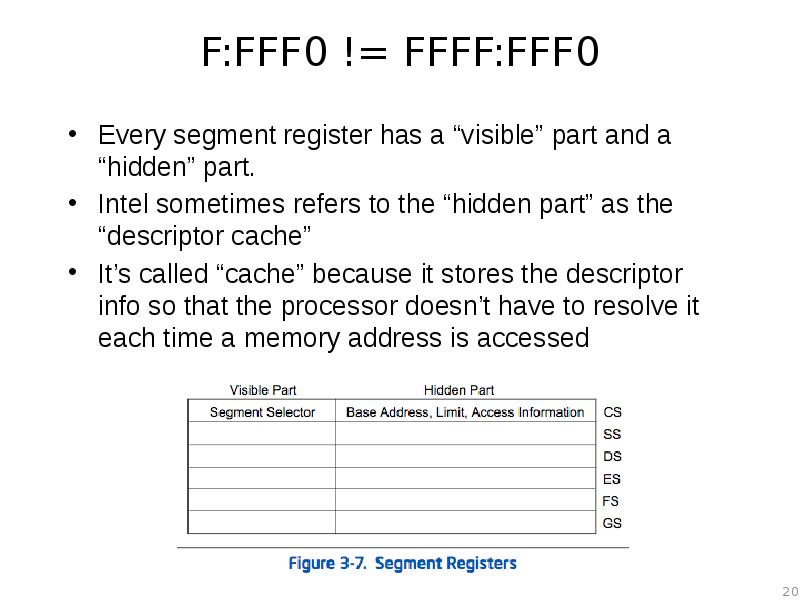

- 20. F:FFF0 != FFFF:FFF0 Every segment register has a “visible” part and

- 21. Descriptor Cache “When a segment selector is loaded into the visible

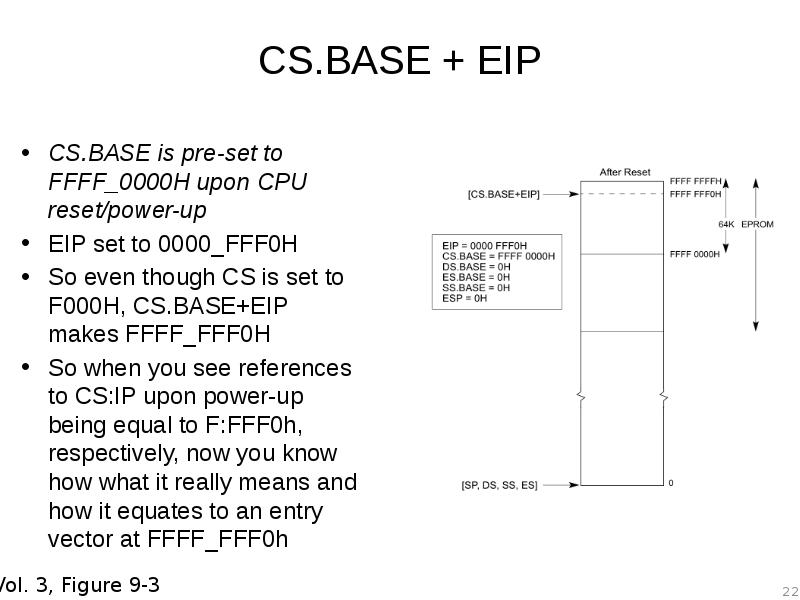

- 22. CS.BASE + EIP CS.BASE is pre-set to FFFF_0000H upon CPU reset/power-up

- 23. Reset Vector So upon startup, while the processor stays in Real

- 24. Analyzing any x86 BIOS Binary With UEFI we can usually skip

- 25. A dream deferred We’re going to hold off on the rest

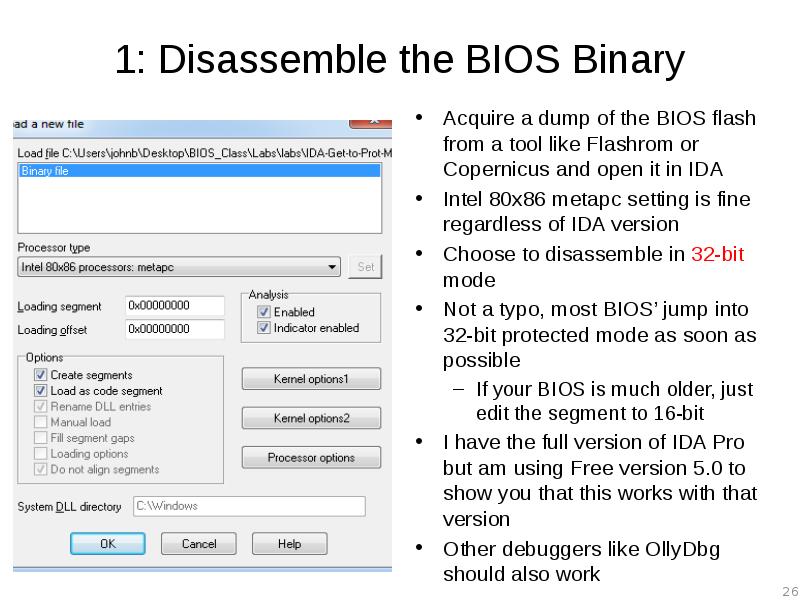

- 26. 1: Disassemble the BIOS Binary Acquire a dump of the BIOS

- 27. FIXME Update procedure for new IDA demo 6.6

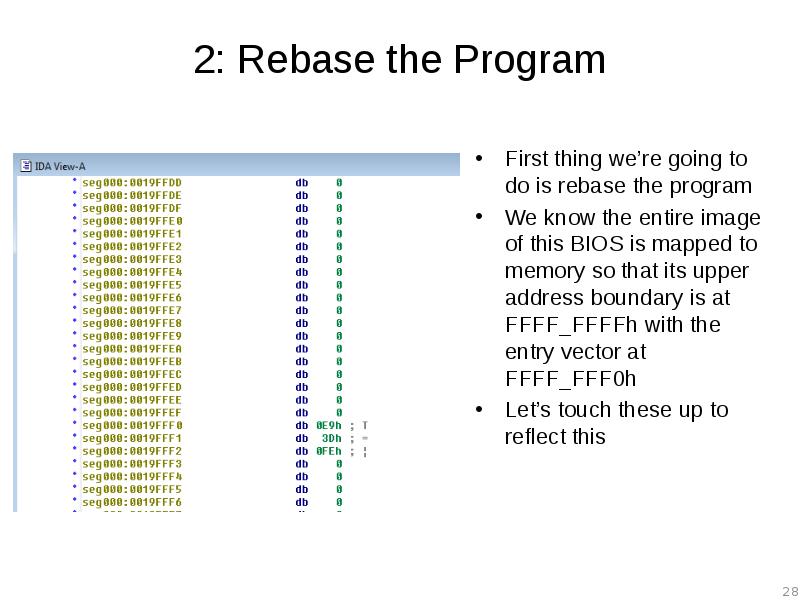

- 28. 2: Rebase the Program First thing we’re going to do is

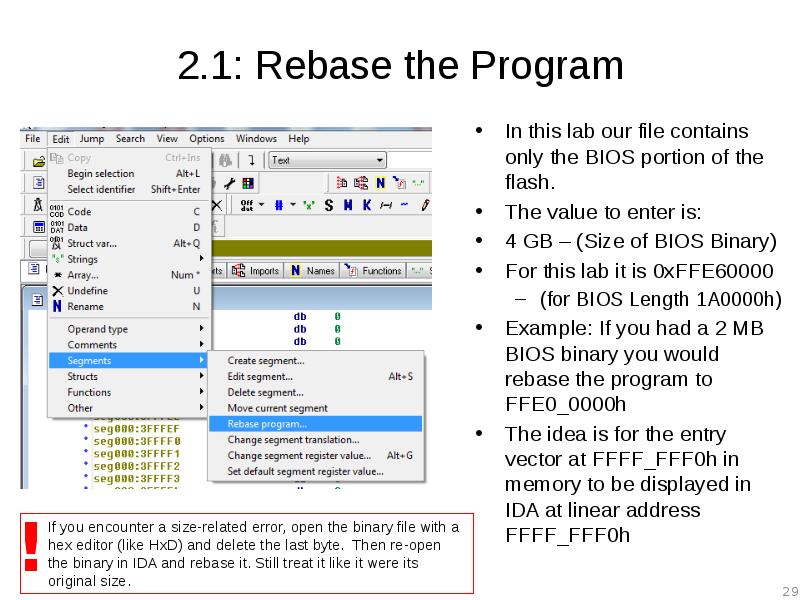

- 29. 2.1: Rebase the Program In this lab our file contains only

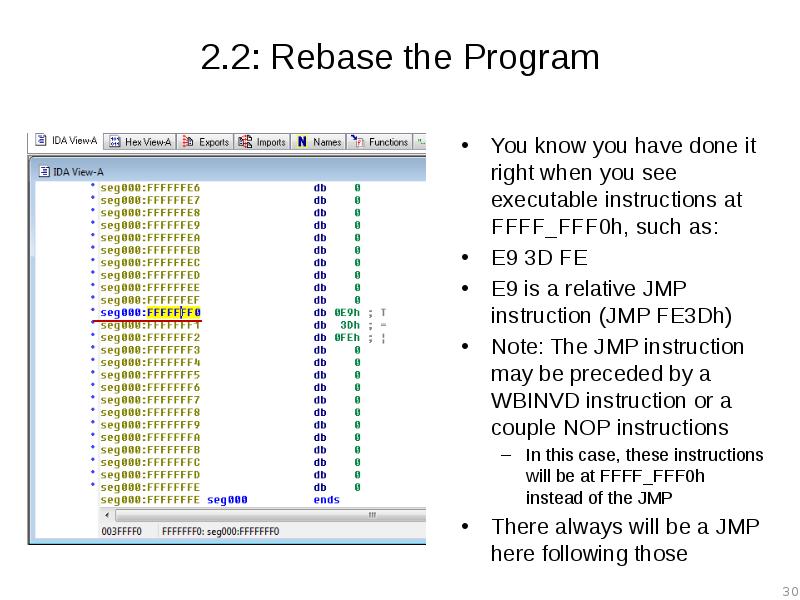

- 30. 2.2: Rebase the Program You know you have done it right

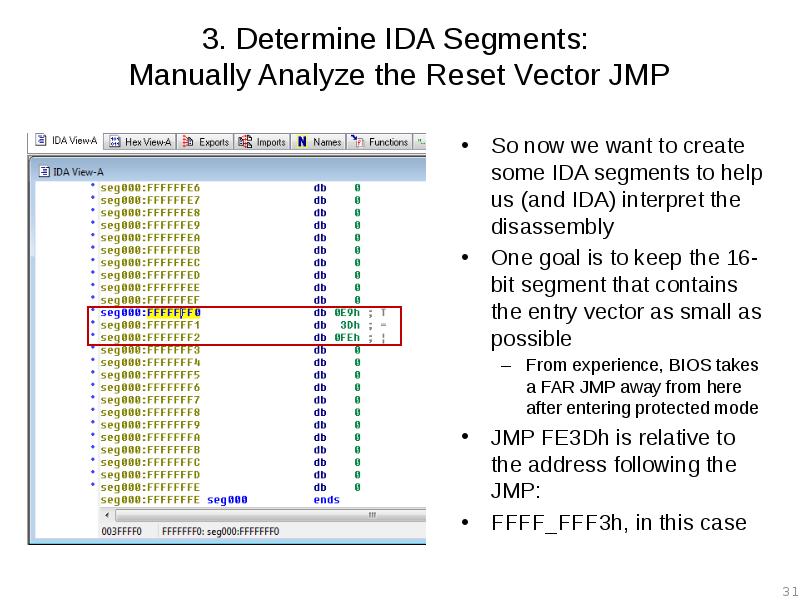

- 31. 3. Determine IDA Segments: Manually Analyze the Reset Vector JMP So

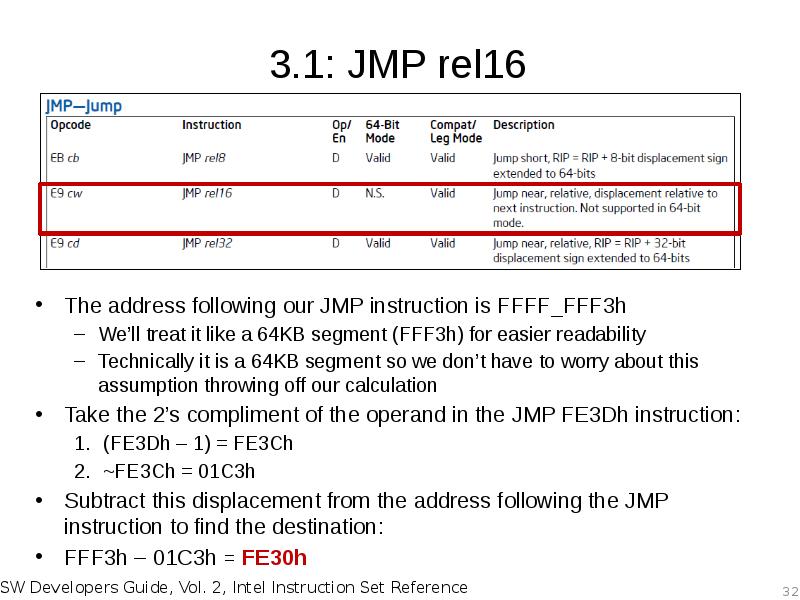

- 32. 3.1: JMP rel16 The address following our JMP instruction is FFFF_FFF3h

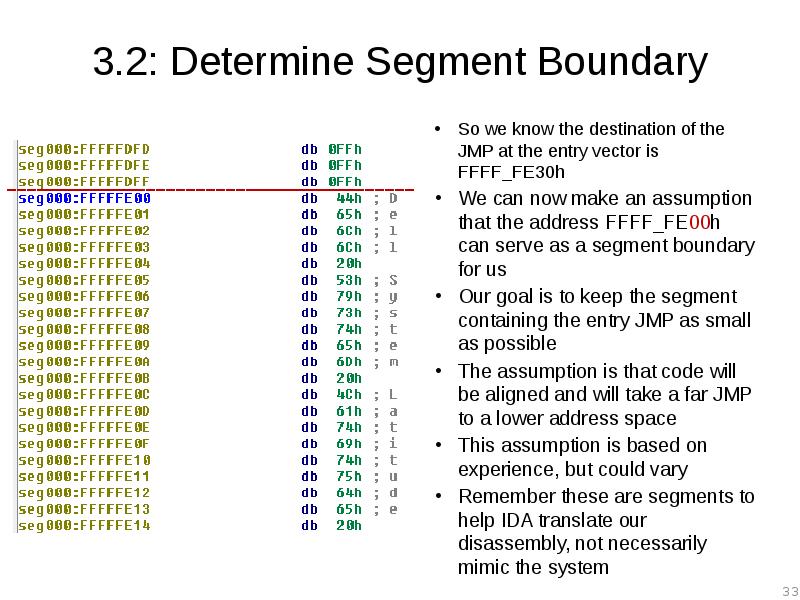

- 33. 3.2: Determine Segment Boundary So we know the destination of the

- 34. 4: Create Initial 16-bit Segment Edit –> Segments –> Create Segment

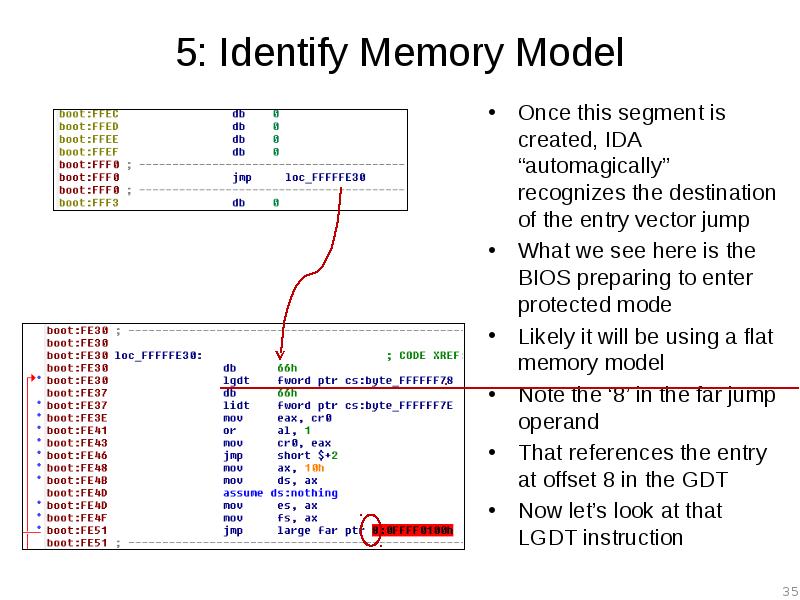

- 35. 5: Identify Memory Model Once this segment is created, IDA “automagically”

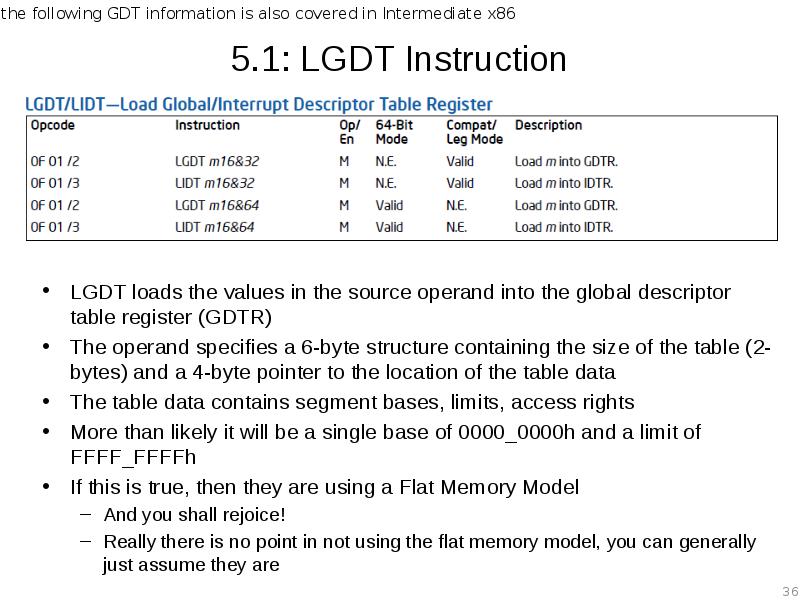

- 36. 5.1: LGDT Instruction LGDT loads the values in the source operand

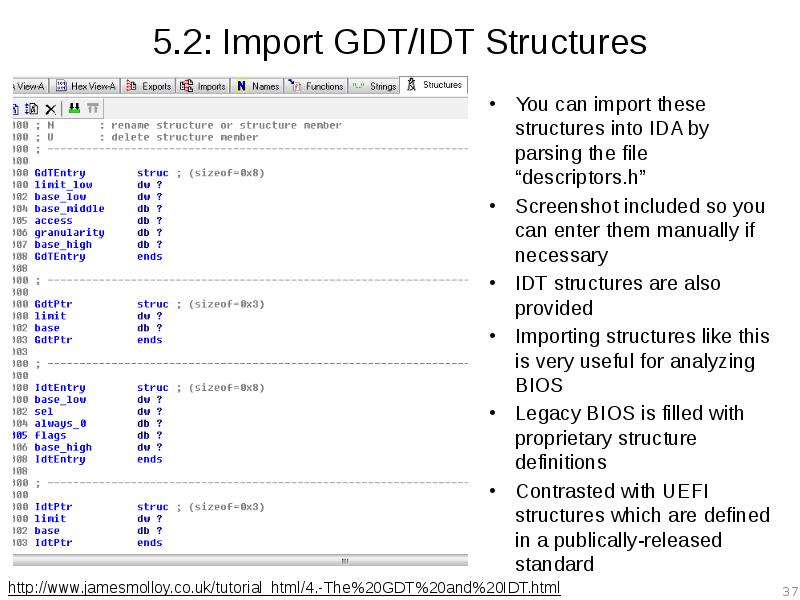

- 37. 5.2: Import GDT/IDT Structures You can import these structures into IDA

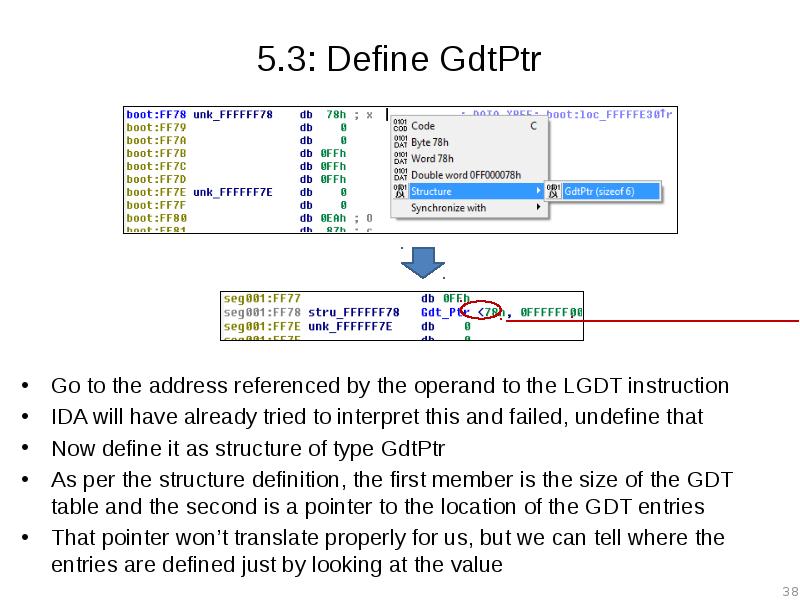

- 38. 5.3: Define GdtPtr Go to the address referenced by the operand

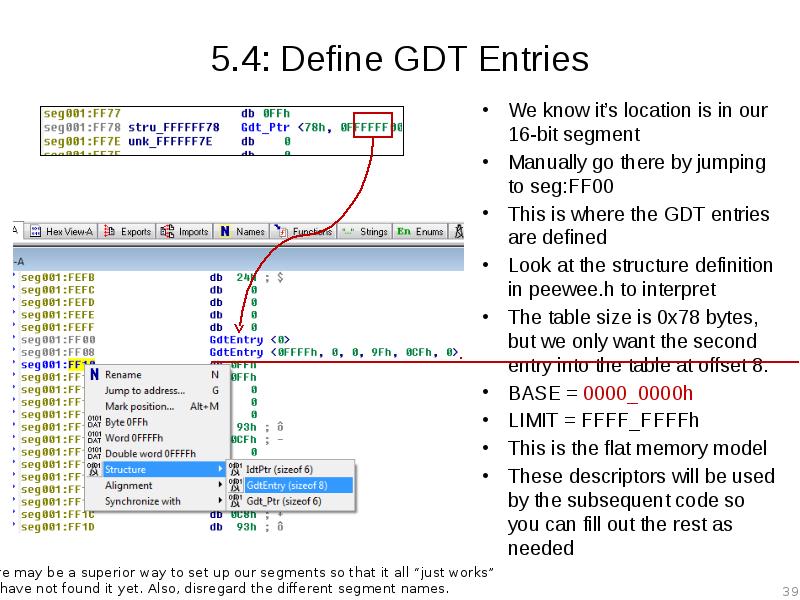

- 39. 5.4: Define GDT Entries We know it’s location is in our

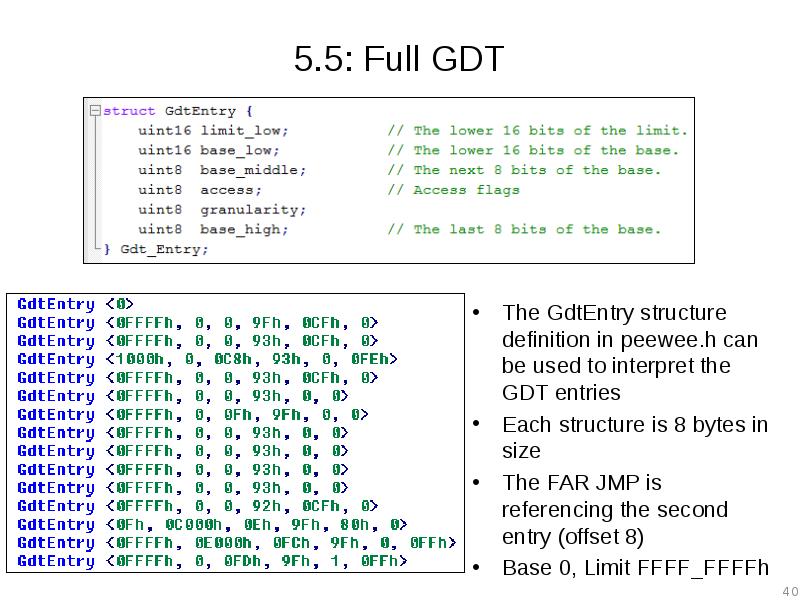

- 40. 5.5: Full GDT The GdtEntry structure definition in peewee.h can be

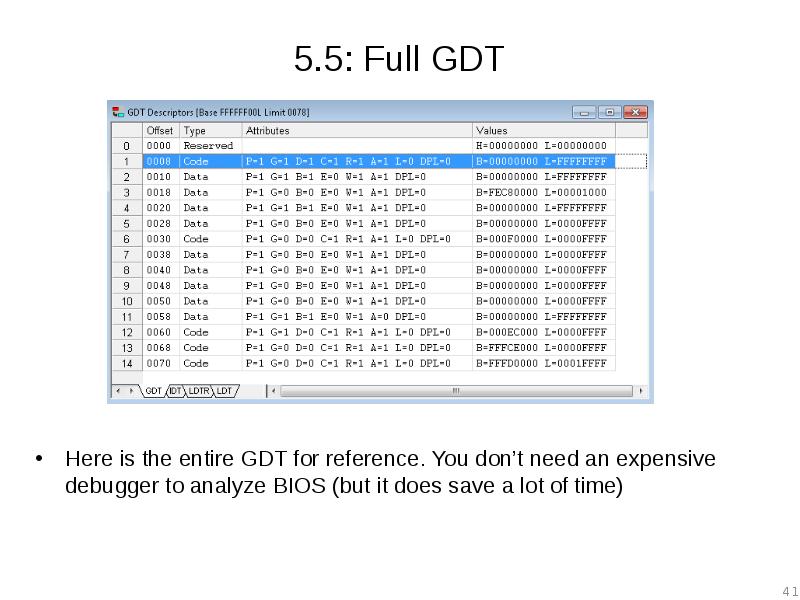

- 41. 5.5: Full GDT Here is the entire GDT for reference. You

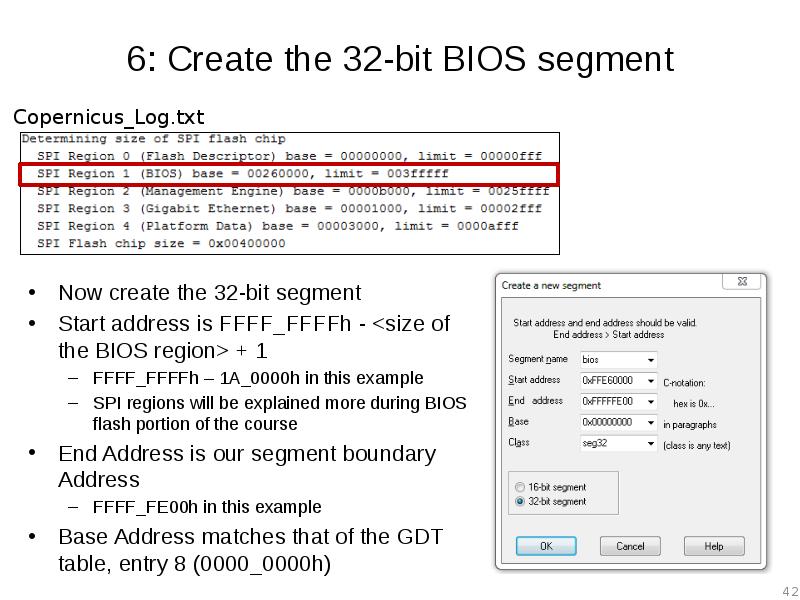

- 42. 6: Create the 32-bit BIOS segment Now create the 32-bit segment

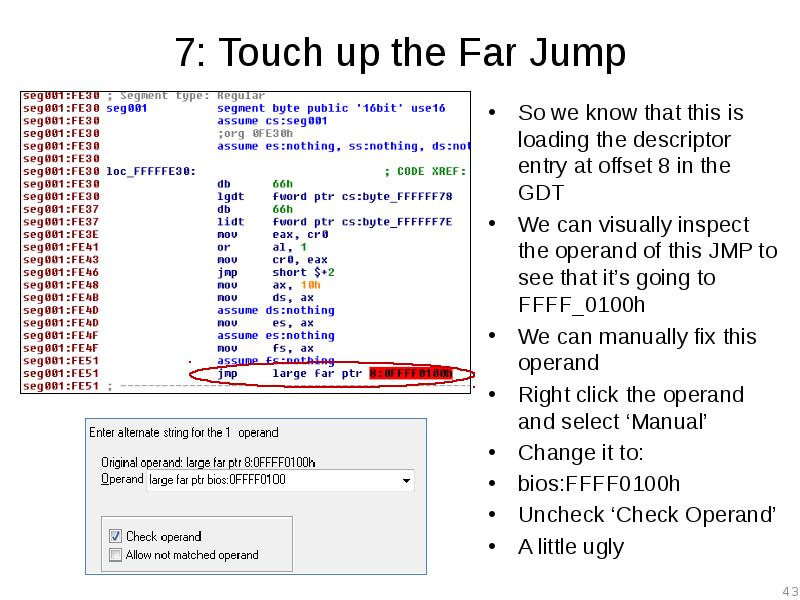

- 43. 7: Touch up the Far Jump So we know that this

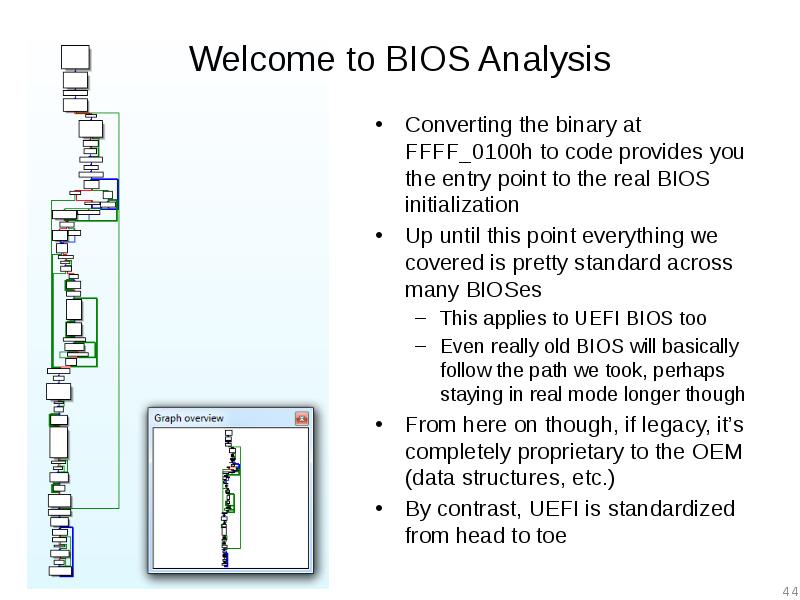

- 44. Welcome to BIOS Analysis Converting the binary at FFFF_0100h to code

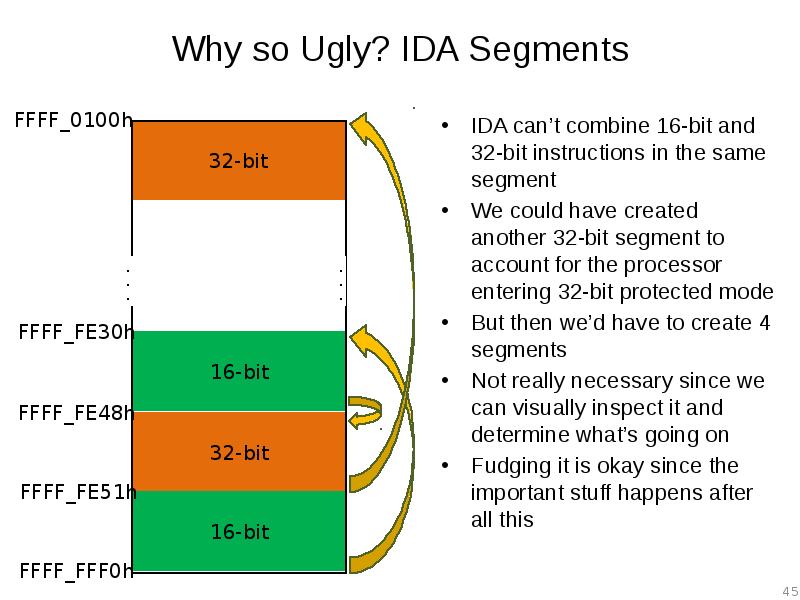

- 45. Why so Ugly? IDA Segments IDA can’t combine 16-bit and 32-bit

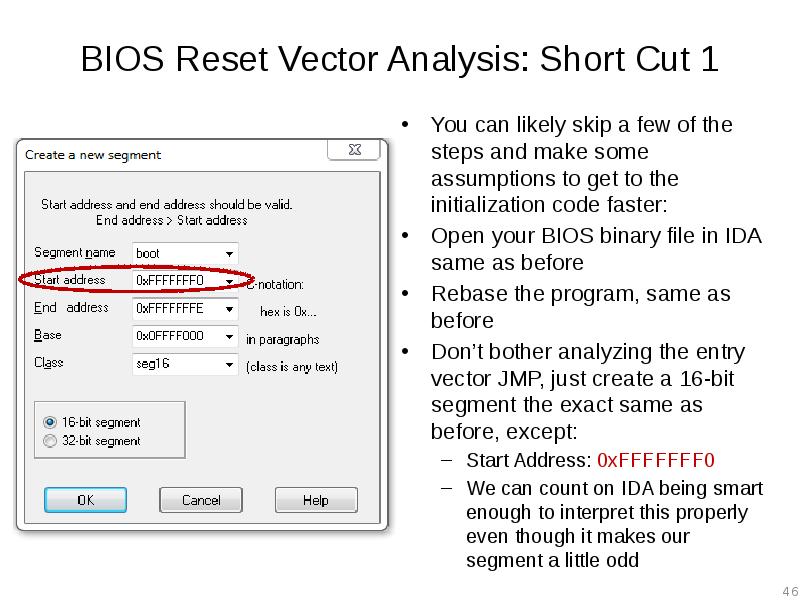

- 46. BIOS Reset Vector Analysis: Short Cut 1 You can likely skip

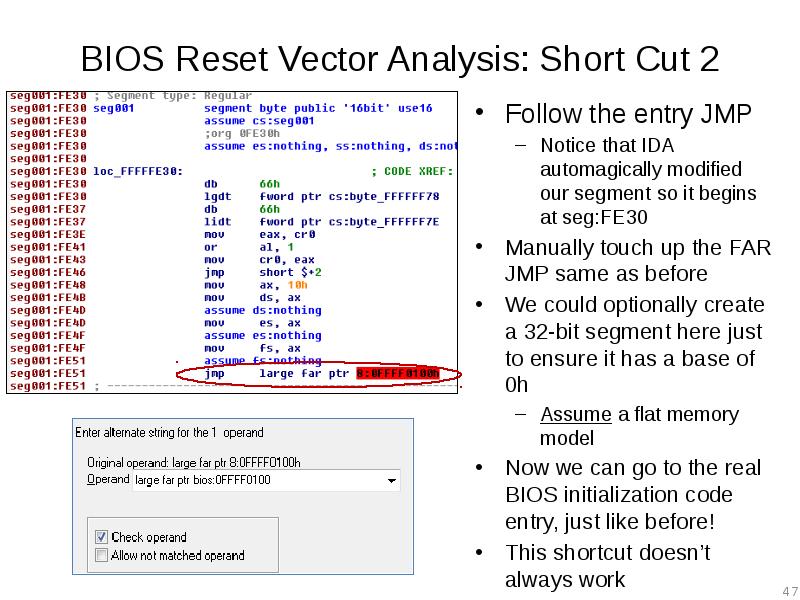

- 47. BIOS Reset Vector Analysis: Short Cut 2 Follow the entry JMP

- 48. Lab: Scratch the surface Repeat the process we just did for

- 49. Скачать презентацию

Слайды и текст этой презентации

Скачать презентацию на тему Advanced x86. BIOS and System Management Mode Internals Reset Vector можно ниже:

Похожие презентации